Did Women Use Knitting to Send Secret Messages During the War?

I recently read an interesting Facebook article explaining how women during wartime secretly communicated messages through their knitting, using different stitches to pass on coded information. I looked further and found many articles that claim:

- Phyllis Latour Doyle chatted to German soldiers, then opened her knitting kit and added knots to the silk yarn to be knitted into a jumper.

- American Elizabeth Bentley passed information to the Soviet Union during World War II by transporting it in her knitting bag.

- Local women living near the railway lines during The Belgian Resistance (WWI & WWII) were recruited to watch German trains. They used a specific “stitch code”: purl stitch represented one type of train, dropped stitch (a hole) represented another etc. These “knitted journals” were then passed to the resistance to track enemy logistics.

I really loved the idea; the thought of a quiet resistance, ingenuity, and domestic skills being used for espionage.

Unfortunately, further investigation has not revealed anything to support the claims that hidden messages were actually knitted into items.

While women absolutely played vital roles during World War I and World War II, and knitting was a widespread activity, there is no reliable historical evidence that knitting stitches were used as an organised or recognised method of secret communication.

The reality of wartime knitting

Knitting during the wars was common and women were encouraged to produce socks, scarves, gloves, balaclavas, and other items for soldiers serving overseas. Governments and aid organisations distributed approved patterns that were practical, standardised, and designed for warmth and durability. Knitting circles also became an important way for communities to contribute to the war effort.

During WWII, the UK and US imposed strict postal censorship that resulted in certain printed materials, including technical diagrams, instructions, and patterns, from being mailed overseas. The concern was not specifically knitting, but the possibility of any coded diagrams or technical drawings being used for espionage.

Women and wartime intelligence work

Women were involved in espionage, resistance movements, and intelligence gathering. Many served as couriers, radio operators, codebreakers, and informants. Some used everyday activities as cover for their movements, including shopping, cycling, or sitting in public places. But according to available evidence, not encoding messages in knitting.

Historians of espionage and cryptography have found no documentation showing that knitting itself was used as a method of encoding or transmitting messages. There are no military records, resistance manuals, personal diaries, or surviving examples that support the existence of stitch-based codes.

Why the knitting code story doesn’t hold up

From a practical standpoint, the idea of knitting as a messaging system raises several problems:

- Knitting is a relatively slow process, making it impractical for time-sensitive information

- Stitch patterns are difficult to standardise and interpret accurately

- Errors would be common and hard to detect

- Messages could not be easily updated or corrected

- Anyone could copy the pattern without understanding its meaning

Wartime intelligence relied on methods that were faster, more reliable, and easier to conceal, such as written ciphers, invisible ink, microdots, coded language, and radio transmissions.

Why the myth persists

The idea of secret knitting codes continues to circulate because it is appealing. It highlights women’s contributions, reframes domestic labour as subversive, and offers a romantic image of quiet resistance. Social media has allowed the story to spread widely. There are documented cases of women appearing to knit innocently while also gathering or observing information, and this overlap has helped fuel the persistence of these stories.

The story of wartime knitting codes is a modern myth, not supported by historical evidence. The truth is no less impressive: women found countless ways to support, resist, and endure during the wars, even if their knitting needles were used for warmth rather than wartime messages.

Surely it was all a secret

It is sometimes suggested that the absence of evidence reflects secrecy — that women involved in intelligence work took their methods to their graves. However, while many wartime activities were classified, other secret operations have since been extensively documented. To date, no archival records, physical examples, or firsthand accounts support the existence of knitting-based communication systems.

Actual Ways Knitting Can Carry Meaning

Although I found that knowledge a little disappointing, there are genuine ways knitting and fibre arts have been used to deliberately represent information. For example, my friend is knitting a temperature blanket for each of her grandchildren.

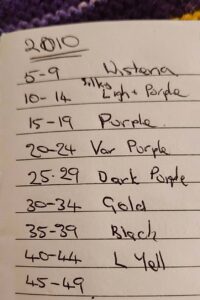

Temperature Blanket

A temperature blanket is a knitted or crocheted project where each row (or square) represents the temperature for a specific day. The maker chooses a colour scale in advance, and the colour used for each row corresponds to that day’s recorded temperature.

Over time, the finished piece becomes a visual record of weather patterns across a season, or a full year. Each row represents the temperature of the day, with different colours showing how warm or cool it was — a knitted record of the year’s weather.

While there’s no single “correct” method, most people follow a similar approach:

While there’s no single “correct” method, most people follow a similar approach:

- Two rows = one day

- A temperature range is assigned to each colour

- The day’s temperature determines the colour used

The rules are personal and flexible. Some people track the daily maximum temperature, others use the average or top temperature, and some even track rainfall instead.

Temperature Blankets are a form of data visualisation through fibre art, and are knitted for several reasons:

- They turn abstract data into something tangible

- They create a meaningful keepsake of a specific year or time period

- They encourage daily creative habits

- They combine craft with mindfulness and routine

- They tell a personal story — where you lived, how the year felt

In this sense, they can be considered a deliberate way of encoding information into a crafted project.

Aran knitting patterns

Traditional Aran jumpers are often said to encode family identity or personal symbols. While many modern stories exaggerate this, some patterns did apparently have:

- locally favoured motifs

- symbolic names (cables, diamonds, honeycomb)

- regional styles

Andean textiles (quipu-adjacent culture)

In Andean cultures, textiles often carried:

- social status information

- community identity

- ceremonial meaning

Quipu used knots rather than knitting to record numerical data. reinforcing the idea that fibre can function as a medium for storing information.

Mourning textiles

Some Victorian-era knitted or embroidered items incorporated:

- dates

- initials

- symbolic colours

These functioned as memorial records rather than secret messages.

Protest and political knitting (modern)

Craftivism uses textiles to:

- make visible statements

- communicate values

- provoke discussion

Examples include:

- banner knitting

- slogan scarves

- symbolic colour use

Textiles work well as methods of communicating meaning because they are:

- slow and deliberate

- repetitive

- symbolic

- portable

- emotionally meaningful

That makes them perfect for:

- recording

- marking time

- expressing identity

The common thread

Across cultures and centuries, fibre arts have been used to store meaning openly, not to hide secret messages. They tell stories, mark lives, and record patterns.